An America-less Internet

Nine out of the ten most visited websites in the United Kingdom are those operated by US organisations. The same cannot be said for the flip side. There are zero UK-operated websites found in the US’s top 50. Our accents are being adopted, but our websites are certainly not. They are as spiceless as our beige cuisine (But god I do love fish and chips).

This isn’t a gripe about where the UK sources its web from. Far from it. The web is a big beautiful collection of interconnected networks. Being able to access ideas, services and products from across the globe, in the time it takes to blink, is a thing of beauty. I’ve been lucky enough to explore the Internet since Geocities was a thing. The web is going through a rocky period of trustworthiness. With the ease of access to generative AI this may get worse before it hopefully gets better. For the most part though, I still believe the Internet is a source of good.

As with physical life, we spend our digital lives in certain social spheres. Not as geographically bound as our real-life selves, but still loosely bound by our language, interests and existing communities. The joy of the internet is being able to traverse other spheres with minimal effort. Yet for the most part, the Internet you know will overlap with the Internet I know. You’re reading a software engineers blog, so the likelihood is you’ll spend a chunk of your time where I spend my time. GitHub, Reddit, Google, Discord, Slack, etc. The web is more vibrant and accessible than ever. Yet it’s more homogeneous as people congregate in super-communities like Reddit, Facebook and Discord.

A large chunk of the Anglo-speaking sphere I experience originates and is operated by American organisations. Within this sphere, we all feel any disturbances or changes made by the major players. We are all affected when an AWS data centre goes down. Our combined productivity goes down when Google publishes an enticing doodle. Any dint to Facebook’s SLA and we all find out as it hits the mainstream media.

Whether access to the internet is a right or not, what I have access to is not guaranteed. I’m not expecting there to suddenly be a US-shaped hole in the routing table, but what if? Exactly how screwed would I be?

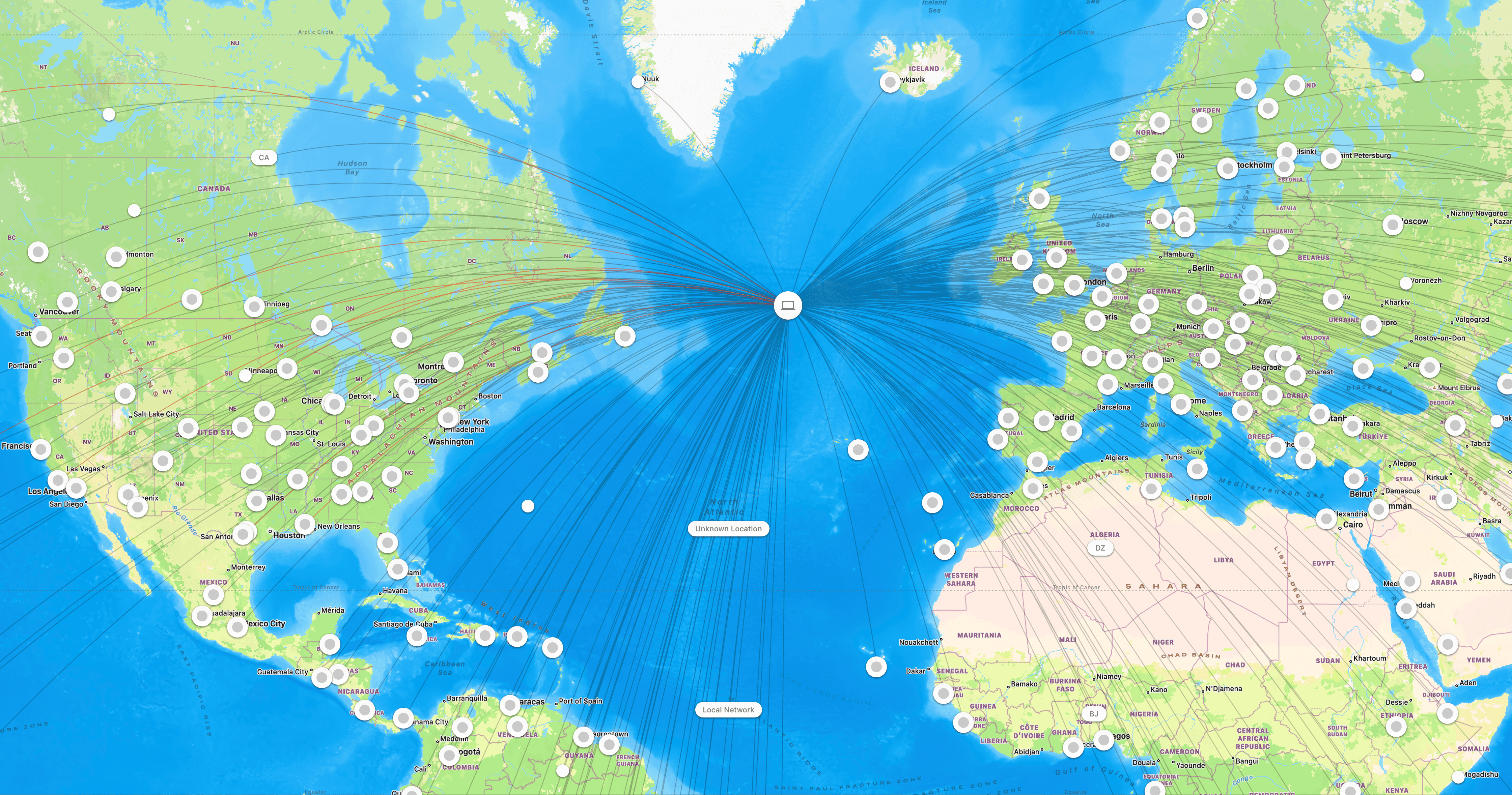

The LittleSnitch map view and a whole world of connections.

The LittleSnitch map view and a whole world of connections.

One does not simply remove the United States

This section talks about IPs and IP geolocation. If you don’t care about that, and just want to know how the experience panned out, skip to the next section.

There are approximately 1.5 billion IPv4 addresses associated with the United States. To keep things simple we’ll ignore IPv6. Just like the majority of the internet. I’ll be using LittleSnitch to block all local traffic heading to the States. An approach that comes with a couple of caveats. First we’ll need to touch on the dark art of IP geolocation.

LittleSnitch blocking 1.5 billion IP addresses.

LittleSnitch blocking 1.5 billion IP addresses.

Which IPs are “American” depends on which geolocation service you ask. IP geolocation is primarily determined by updates published by the Regional Internet Registries (RIR). For a given block of IPs, you can determine a country and maybe some geographical coordinates. This data tends to be the assigned organisation headquarters. So a block of IPs assigned to Google would show the USA as the assigned country. Even if that IP ends up used in a data centre in Dublin. RFC 9092 is looking to improve geolocation data feeds, but its rollout is still a work in progress. After consuming the RIR data, it is up to the geolocation services to use various forms of forensics to improve the accuracy of their results. They are looking for any way to hoover up information about a given IP and its current location. Data mining, data sharing, data analysis and straight-up guesstimates with varying degrees of accuracy. Throw in the fact IPs are always being reassigned, these services have got their work cut out for them!

For example, I’m a user originating from an IP block assigned to the ISP Hyperoptic. With that knowledge and the RIR data, a geolocation service would be confident that I originate from the UK. After that, it’s a case of discovering any evidence to improve the granularity of my location. Have I entered my location (postcode, city, etc.) into a website connected with or owned by a geolocation service? Has my access point been picked up by a Wi-Fi positing system? There are claims that country-level accuracy is over 95% and city-level is over 60%. At the time of writing, geolocation services are 100% right about my origin country, but only 30% correct about the city.

IPs assigned to data centres are a little different. Servers don’t typically roam around the internet like a person does. Leaving breadcrumbs for location services to find. Instead, IP ranges are either published freely or geolocation services have to find this information out for themselves via other means. Amazon and Google, for example, both publish the IP ranges in use and which region the range is assigned to. Freely published data like this isn’t always available though.

So the caveats of this approach. Firstly, IP geolocation is not always accurate. An IP assigned to a server running on AWS may be tagged as operating in the US because the RIR record says so. If the geolocation service has dug deeper, it might more accurately determine its location as somewhere else. So I’m looking for a dataset that represents the physical location of the IP, not the company itself. This leads to the second caveat.

The second caveat is that I’m assuming if America disappeared from the internet, that global data centres would continue to operate. For example, the BBC is predominantly hosted in AWS eu-west-1. If the American AWS regions were to become inaccessible, then we’d expect the BBC website to still work. If AWS as an operating entity was to suddenly disappear, then we’d be left with a lot more spare time on our hands. We’ll assume this hypothetical block is around the physical borders of the USA and not a full blackout of American companies. This is a big caveat as I have no idea how the wider Internet would react to such a fundamental change. We’ll touch on the impact of CDNs and Edge Networks later.

With that in mind, this experiment will use the IPInfo.io dataset to generate the blocklist. A noddy example of how the datasets differ would be www.google.com, which currently resolves to 142.250.187.196. IP2location and MaxMind, at the time of writing, suggest the resolving country is the USA. We’ll assume that Google is hosted regionally and IPInfo reporting the location as London is likely to be correct. It’s a gut feeling, but IPInfo is the way forward today.

The blocklist I’ll be using can be found on GitHub.

Enable the blocklist!

The blocklist is prepared. My connection is ready. For the dramatics I have the Surface OST playing in the background. It’s time to say farewell to the States. For a little while at least.

LittleSnitch doesn’t seem too happy at first. The UI has slowed down processing those 1.5 billion addresses I’ve just flung at it, and my CPU is heating up. I wait for a minute and finally, calmness.

Too much calmness! No outbound connections are resolving. Zilch. Requests are hanging and the start of this experiment is going poorly. My music is still playing at this point though. A red-herring? Probably.

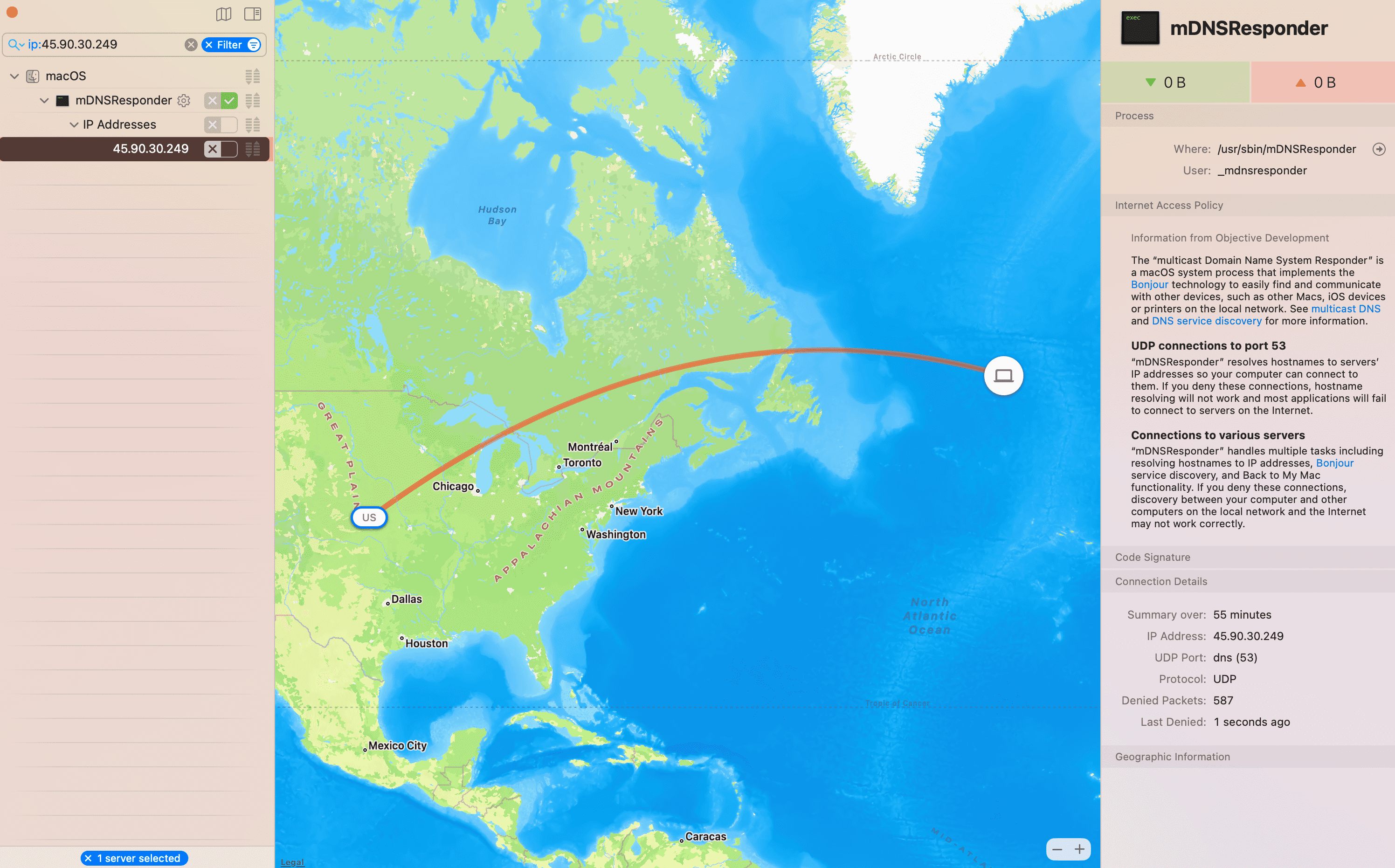

As with most of life’s problems, it’s DNS. I don’t know what DNS service I’m using, all I know is 45.90.28.249 and 45.90.30.249 are now blocked. House points if you immediately recognise the IPs. I should have known! I’ve effectively blocked out the world until I find another DNS provider. The easy ones to remember, 1.1.1.1 and 8.8.8.8, are also hosted in the US. It’s been a while, but it’s back to my ISP’s resolvers for now.

LittleSnitch blocking outbound DNS, essentially blocking everything.

LittleSnitch blocking outbound DNS, essentially blocking everything.

With the DNS config updated, Google now loads. That’s a relief. Let’s find out which DNS service I was using. I’ll search for an IP lookup tool and make quick work of this. It’s no longer a click away as it used to be though. It turns out nine out of ten IP lookup tools returned by the Google search are blocked. Why does the US have such prominence in the IP lookup space?! Thankfully https://tools.keycdn.com/geo exists somewhere in Germany. Turns out I enabled NextDNS at some point. A fantastic DNS service for blocking all kinds of nasties. I’d have to go back to using a pi-hole if America was more than just a tick-box away.

Google is back but my music has streamed its way out of its cache and into silence. Time to start digging into what of the internet is left

The same old internet

From the perspective of the top ten UKs most visited, this new internet operates mostly as it did before. Google, YouTube, Facebook, Instagram, Wikipedia, Amazon, and eBay, all work. At least on the face of it. The only one to have issues is Twitter. The home page loads, but the abs, api subdomains and t.co domain are now blocked. Who knows if this is a recent change to their network topology. I’m just experiencing Twitter how the rest of the world will in a year or so.

I miss the fail whale.

I miss the fail whale.

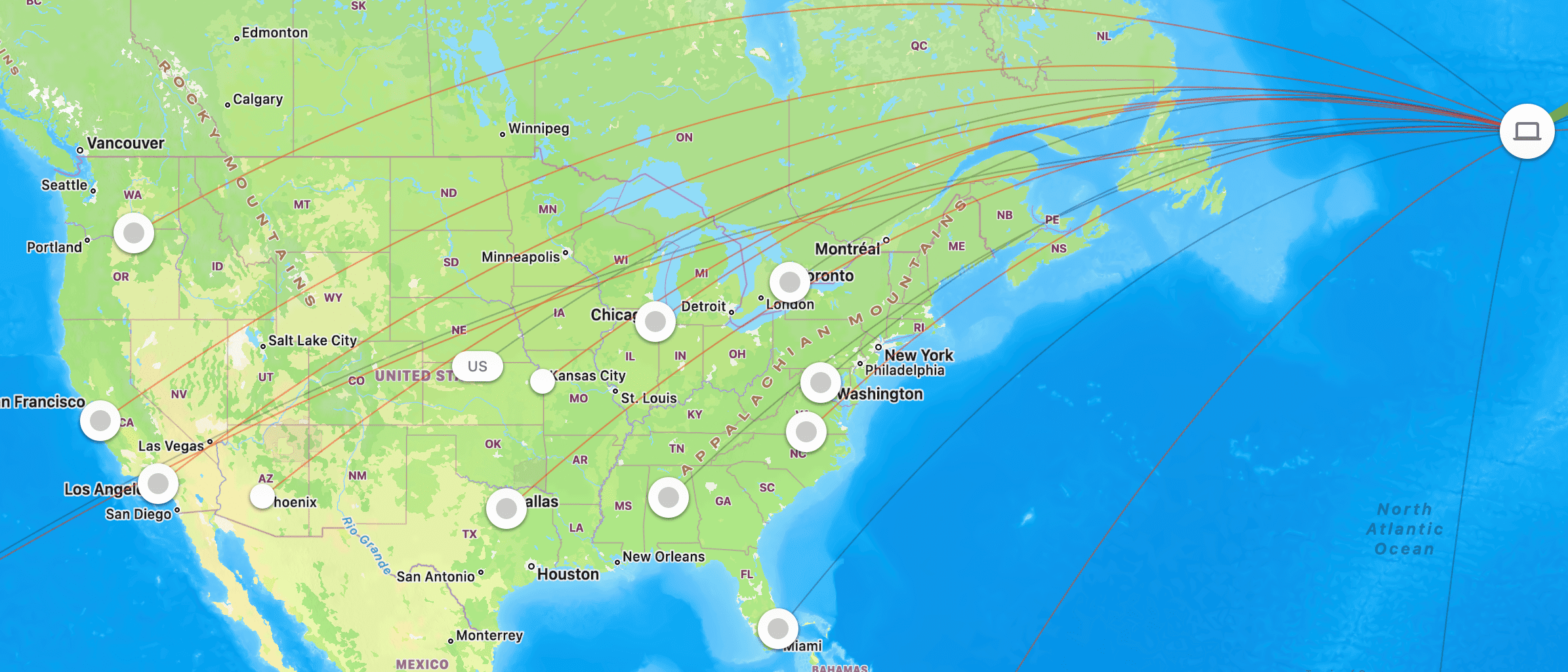

That’s all well and good for the most visited, but what does day-to-day look like? LittleSnitch is blocking plenty of traffic still, so I want to understand what’s quietly trying to connect and failing to do so. No apps have thrown up an angry errors yet, so we’ll have to do some digging.

There’s more to the internet than the top 10 most visited.

There’s more to the internet than the top 10 most visited.

Day-to-day surfing

I’ll start, like most days, by checking my email. My Gmail account is working just fine, whilst Fastmail and iCloud Mail, and their equivalent websites, are now inaccessible. Given Fastmail is an Australian company focused on privacy, I was somewhat surprised by their servers being hosted in New Jersey and Washington and nowhere else.

Being an Apple ecosystem citizen, I’d be cancelling my Apple One subscription if this experience continued long term. Music, News, Mail, and the App Store are no longer usable. I say I’d cancel my subscription, but I wouldn’t be able to access my Apple ID to cancel the payment in the first place. Don’t worry though, it’s not all doom and gloom. Apple TV+ still works…

Something that took me off guard is 1Password. I ❤️ 1Password. Even after it focused on subscription pricing. Its UI, syncing and cross-platform support work perfectly for my needs. Fortunately, my pre-synced secrets are safe and accessible. Unfortunately syncing and account management are not. My data is now out of my control. I’m sure those of you who argued against the hosted/subscription model will be feeling quite smug right now!

GitHub, like Twitter, serves the initial website content from a regional location, but for me, the static assets are now blocked. Any kind of assets from githubusercontent.com such as JS files, images and styles, are all blocked. That results in a difficult website to navigate, but at least the content is available. The SSH git URLs continue to work, so I can still carry out my day job. Github.io is completely blocked, so I can’t even read my own blog as it’s a GitHub Pages deployment. The irony is not lost on me.

If you’re thinking “Maybe I’ll use GitLab locally instead”, not via the now blocked GitLab website you wouldn’t. They’re kind enough to mirror GitLab CE on GitHub though. GitHub is a massive store of incredible open-source software. The loss of it would be felt throughout the development community and further afield. On the plus side, the Arctic Vault is an international demilitarized zone. We could bust that open and get the 2020 GitHub snapshot. I’d imagine there are a whack of security patches that would need applying first.

Speaking of losses to the developer community. W3C, Stackoverflow, Quora, HackerNews, dev.to, Hacker Noon, Hashnode, CodePen, Leetcode, Neetcode, Coder Dojo. All Gone. US software engineers would have the competitive advantage of still being able to Google an error string and access the answer!

Netflix is the same story as Twitter and GitHub. The initial document loads and so does the odd bit of content, but that’s it. It’s broken and attempting to stream anything results in a blank screen. How will I now watch Brooklyn 99 for the umpteenth time now!? I’d naively assumed given the regional restrictions Netflix has on content, that the content would be physically closer. Maybe it is, but the website isn’t letting me near it.

Netflix not loading correctly :(

Netflix not loading correctly :(

Things Sync. DayOne. Portal. Plex. PocketCasts. Even Signal (but not WhatsApp). All are unavailable in this ever-frustrating internet I’ve imposed on myself. Plex is more frustrating given I’m running the server on the very same machine I’m typing this on. I just can’t log in via their auth service. It’s not the end of the world, I can authenticate local access with a little config change. If not, I would have to go to opening my content without a fancy UI and metadata. What kind of world is that?

I thought I’d be less distracted given Reddit, the epicentre of my particular internet bubble, was completely blocked. Returning to it the following day though, and it’s back. No matter how much I try, it just won’t let me quit. (Update: It turns out Reddit is using Fastly, just like Last.fm is. See below.)

Given my music stopped about ten minutes into this experience, the last thing I’ll check is Last.fm. Unfortunately, the audio scrobbling API service doesn’t work. Originally a UK company, it was bought out by CBS back in 2007. With Apple Music unavailable and Spotify.com also blocked, then it’s not like I can listen via streaming anyway. Maybe Last.fm made a sound decision. Maybe I shouldn’t have given away all my CDs.

The DNS records for Last.fm do help to highlight an issue with the approach of blocking IPs by country. Accessing https://www.last.fm works, whilst https://last.fm does not. The difference being the www subdomain is CNAMED to point to the Fastly.net global edge network and resolves to an IP in London. The apex domain points directly to a Google data centre in Missouri, as recommended by Fastly. As with any content delivery network, I’m being served from a host nearby, but the canonical server could be hosted elsewhere. If Last.fm is hosted in the US but makes use of a CDN, the experiment shows a working website, but in reality, Last.fm would be unavailable if the US was really truly off-grid.

Welcome back, America

Enough is enough! Let’s wrap this up. I need my Internet back.

A key takeaway from all this is the geographic flexibility of large tech companies. Regional laws and requirements are manageable when you have millions of dollars in the war chest. From opening new data centres, deploying across multiple locations and covering the operating costs of those regions. Those normal-sized companies, start-ups and everyone else in between don’t always have the financial freedom to cover the costs of a multi-region system architecture. A CDN and Edge Networks can get you so far, but without multi-region deployments, you’re still limited to your origin location. Most companies need not worry about physically deploying to other continents though. For the most part, that works, and it has given us the web we have today.

One of the few constants in life is change. We can’t assume the internet as we use it today will last for the foreseeable future. The Internet is the most impressive distributed networks of our time. Yet its fragility isn’t in the technology itself but in the politics, geography and laws that encompass it. Do I expect America to disappear? No, of course not. If it did, I think we’d have bigger problems to worry about than access to Netflix. The internet will change though. The spheres of influence and networks of communities will shift with time. We need to be mindful that it’s shifting in the right direction, continuing to encourage creativity, collaboration and openness. With maybe some more redundancy baked in!